Image courtesy of the British MuseumStudies in Witchcraft and the Occult: it’s a popular course for University of Alberta students from all faculties and years of study, and it isn’t hard to imagine why. Just the name is intriguing, mysterious. It calls to mind everything from reading Harry Potter to learning about the Salem witch trials in grade school. But what exactly does it mean to study witchcraft? I sat down with Witchcraft instructors Lara Apps and James White to find out.

Witchcraft studies are historical in a broad sense.

Image courtesy of The Ghost DiariesWitches have been around for a long time. The U of A’s course covers a historical period of 2500 years or more, often starting in Ancient Greece and ending today (yes, today — but more on that later). Throughout this period, witches and witchcraft change dramatically. In Ancient Greece, witches often appeared as beautiful women who drew their powers from the gods. Contrast this image with that of Early Modern Europe, where inherently evil witches fornicated with the devil, and the diversity of representations begins to emerge. As a result, James White takes a “moving spotlight approach” to his course. Politics, religion, economics — his students focus on “whatever seems to be the prominent or defining feature at the time,” he explains.

Witchcraft studies bring new perspectives to other histories…

Image courtesy of MediumPrior to roughly the 14th century, canon law officially claimed that witches did not exist — or at least, that the Church (and Christians) did not believe in witches. This position changed dramatically during the Renaissance. Witchcraft was brought under a Christian narrative as a perversion of Christianity, figuring witches as Satanic servants. Alongside other Renaissance reforms were changes to judicial practices, and a re-popularization of torture that harkened back to Roman systems, White explains. Together with other factors, these changes paved the way for the Early Modern European witch-hunts. Witchcraft brings a very different perspective to the Renaissance. As a witch, White tells his students, you would have been better off in the 11th or 12th century than in the 15th or 16th.

And, that history is changing and evolving.

Image courtesy of northernlightsiceland.comWhen Lara Apps started her own research on witches and witch-hunts, she expected to focus on a largely misogynistic historical phenomenon. She surprised herself. While the overall number of accused witches was predominantly female, she explains, many men were also accused and convicted. In certain regions, such as Normandy and Iceland, more men were accused than women. Apps came to ask the questions: how did gender actually feature in witch-hunts? And why have historians largely ignored male witches? These questions inform her teaching, and led her to co-author the book, Male Witches in Early Modern Europe. Gender is just one area in which former histories of witchcraft continue to be reconsidered and revised.

On the other hand, witchcraft studies aren’t strictly historical…

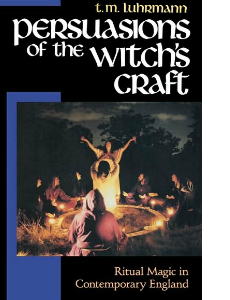

Image courtesy of luhrmann.netWhen it comes to witchcraft, Apps notes, “it’s a modern problem.” Witch-hunts still occur today in regions of Africa, India, and Papua New Guinea, among other places. Apps’ course also covers a text called Persuasions of the Witch’s Craft, a case study of witchcraft in 1980s London that details how “once-skeptical individuals — educated, middle-class people, frequently of high intelligence — become committed to the ideas behind witchcraft” (Harvard University Press). The text helps Apps to pose a serious question to her students: how do we avoid dismissing witchcraft as a third world problem or phenomenon? White takes a different approach to the question in his course: how do we reconcile the persistence of witches and witchcraft, in all their various forms, with the general “age of disbelief” in which we live?

To answer these questions, Studies in Witchcraft and the Occult takes an interdisciplinary approach, bringing together sociology, anthropology, and philosophy.

And often focus on wider social trends.

Courtesy of AV ClubAt times, witchcraft studies seem to move well beyond actual witches into social questions raised by representations of witches. White often screens an episode of the ’60s sitcom, Bewitched, for his class. The benevolent witches of Bewitched, he points out, battle stereotypes and misconceptions about what is an otherwise normal minority group. In the backdrop of 1960s America, White asks his students, how might these witches represent race relations? Apps’ own research has examined terrorism and atheism in addition to witchcraft. She notes thematic links in rhetoric between these drastically different subjects of study, explaining that she broadly studies “people who are viewed as enemies.” As a result, she leads her to students on a broad path of inquiry, asking: “what are those ideas [of enmity] connected to?”

So what exactly does it mean to study witchcraft? Take a course from Lara Apps or James White, and you’ll discover that it’s a little more complex than pop culture and grade-school social studies might lead us to believe.